Ellen Lesperance at Adams and Ollman: We Were Singing

The prevailing ethos of contemporary art embraces the snarky, ironic, and disdainful. In this atmosphere sincerity and sentiment are big risks but Ellen Lesperance emanates both in We Were Singing with refreshing results. The show does not convey a false or easy fuzzy feeling, but rather a hopefulness that the best way to subvert a sexist system might actually be through deep, steady, feminine affection.

Much of the affection in We Were Singing is directed toward recently deceased artist Sylvia Sleigh, who was a central figure in the feminist art movement of the 1970’s. Sleigh was known for realistic portraiture, mainly of friends and compatriots in the movement, such as the members of her women’s gallery co-op A.I.R. She also often painted her husband, art critic Lawrence Alloway, in the nude, reversing the historically established roles of male artist-genius and nude female model-muse. For We Were Singing, Lesperance has remade many of Sleigh’s paintings as Polaroid pictures featuring her own partner Joseph McVetty, directly referencing the original works’ titles and loosely mirroring body positions, props, and composition.

As a regular part of her practice Lesperance identifies textiles present in significant situations of feminist activism — in this instance the paintings of Sylvia Sleigh — and transcribes the visual image of the textile into gridded gouache paintings that act both as a map for a knitted recreation of the textile and a visually autonomous work on paper. Every imperfection and exaggeration in Sleigh’s paintings of these textiles is faithfully transcribed by Lesperance, resulting in asymmetrical patterns with complex and jarring color combinations that seem to vibrate. The points of color-information which make up these paintings translate the aggressively analog activity of knitting but also recall digital pixels and other ways we store and process information. Lesperance’s gridded paintings in particular embody our human impulse to understand through ordering and categorizing.

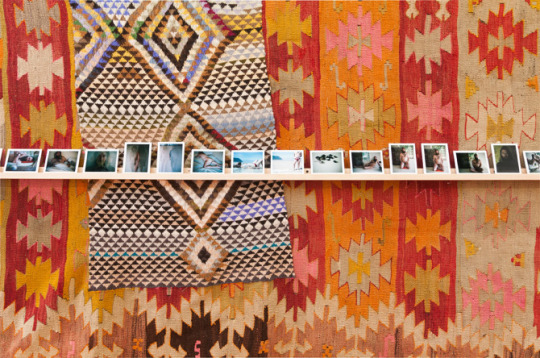

Using one of these gauche patterns, Prop For A Turkish Bath, as a guide, Lesperance recreated the physical textile in the background of Sleigh’s original Turkish Bath painting. Through methodical craft, Lesperance gives value to the re-created object with its endearing imperfection and futile attempt to be the unknowable original. The object, painted by Sleigh, then mapped and subsequently re-knitted by Lesperance, exists simultaneously in four different ways through a kind of ‘telephone game’ process.

Lesperance’s textile translation moves between 2-D and 3-D, between the past and the present, between Sleigh’s location and her own. She shows that a knitted textile can be as much a depiction or rendering as a painting can be an object.

Ellen’s other knitting projects often recreate sweaters rather than flat textiles, and deal with identity and personas, as the wearer of her recreated sweaters assumes the identity of the original subject. Polaroid photographs maintain this element of persona in We Were Singing as Joseph McVetty wears the settings of Sleigh’s paintings and assumes the identity of her subjects.

Lesperance uses the textile as a backdrop in some of the Polaroid photographs, adding a fifth translation of the textile and strengthening the photographs’ imitation of Sleigh’s original paintings. The use of photography seems at first to be out of place in relation to Sleigh’s work, but with closer attention the sensibility of Sleigh’s paintings becomes obvious in the small, glossy compositions. Lesperance uses the tools, people, and settings available to her to recreate Sleigh’s concepts — giving light to both the similarities and differences between their individual frames of reference. The most piercing aspect of these photographs is the palpable intimacy between the photographer (Lesperance) and subject (McVetty). There is a sense of trespass, but perhaps only because we aren’t accustomed to an intimate female gaze made public.

Direct mimicry has always occurred in art, but while male artists like Jeff Koons often copy others with a sense of self-congratulatory machoism in how much they can get away with, Lesperance pays honest tribute, treating Sleigh as a friend, muse, mentor, and confidant.

The result of her direct conversation with Sleigh is twofold: she draws attention to a known, but not canonized, feminist artist of the recent past whose work is still highly relevant, and she highlights the ways in which Sleigh’s context is different from her own contemporary context. She is not afraid to belong to her own time, in conversation with the past. In literally knitting a new textile, she figuratively knits together actions across time, attempting to ensure that the life and work of Sylvia Sleigh is not lost in the past and a male-dominated history.

Lesperance denies common male-centered attitudes at every turn but she is not a “riot grrrl.” While activist actions often sprout of anger and aggression, sometimes rightly so, Lesperance’s resistance sprouts of its opposite: unyielding affection. For textiles, for flowers, for her partner, and most of all for Sylvia Sleigh. She calmly carves space for female sexuality, craft, sentiment, and sisterhood: an action that is more rare than it should be.

To learn more about Adams and Ollman visit http://adamsandollman.com. For more on Lesperance and her work click HERE.

Images courtesy of Adams and Ollman.