Growth and Opening at The Orchards: New Work by Lisa Radon

A short and idyllic drive down Foster and through the quiet countryside will take you to Boring, Oregon, and to The Orchards, a site-specific sculpture garden that lives on the farm property of the Layng family. Founded in 2017, this project began as a way for curator Matthew Layng to endeavor a space where community and public art can cohesively meld. In their two years of programming, The Orchards have been home to just four installations, some of which remain as permanent or semi-permanent works on the property, and which demonstrate Layng’s intentional and considerate curation. In presenting as a “destination” sculpture garden, contemporary art has found new ground amid the tomatos and the corn. This specifically honed curation adds a necessary and measured precision to the work that is installed. As a result, the pieces that are on view at the open-air venue are intended as ones that would remain and grow with the space they are surrounded by. The Orchards most recently became home to new work by Portland-based artist Lisa Radon. Her newest installation, The Gate, first opened on the eve of Saturday, September 8th at precisely 7:34pm: sunset.

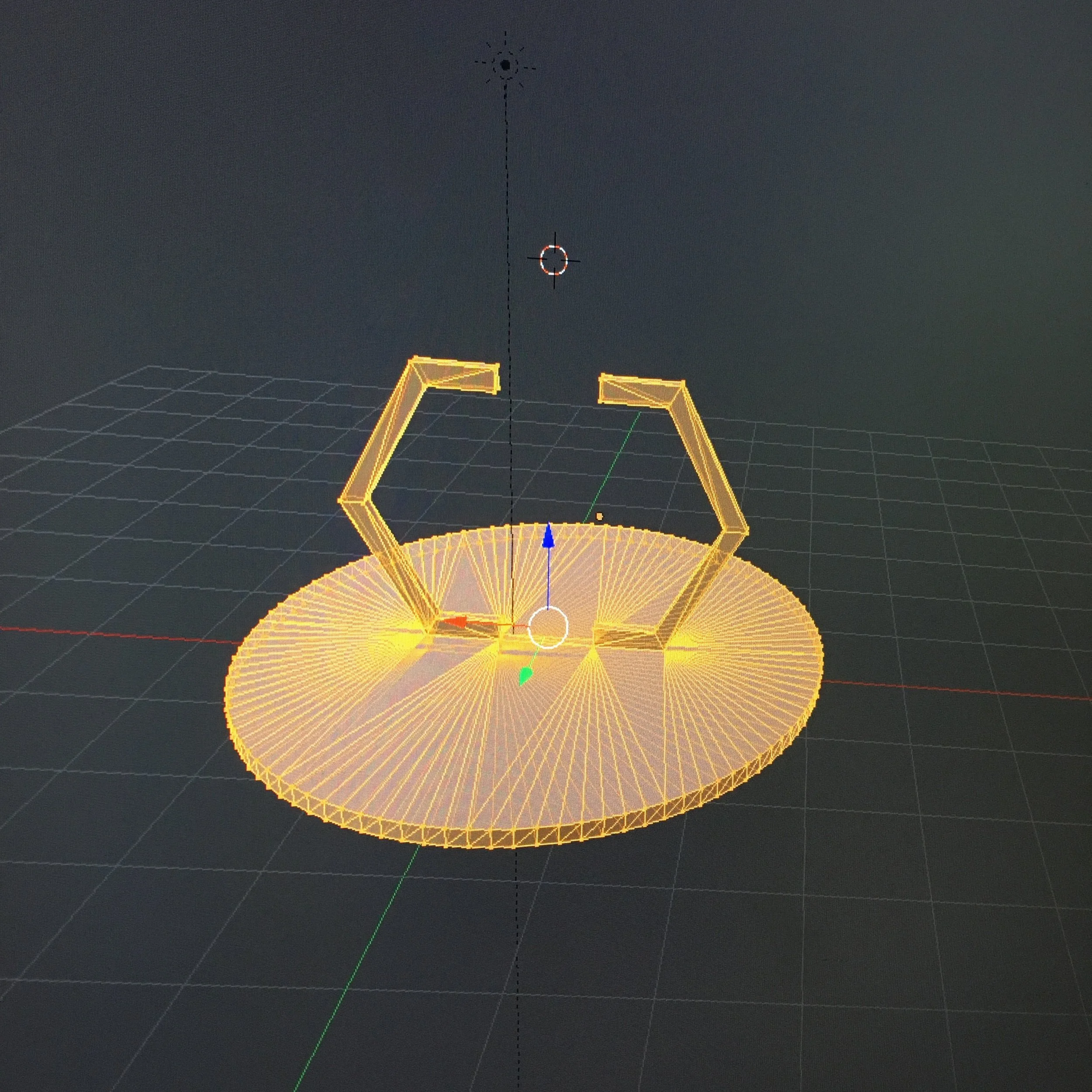

Lisa Radon. The Gate, 2018

The Gate is the result of slow growth and focused energy on the part of both Layng and Radon. Radon’s background in semiology, technology and performativity unite for this piece, which sits prominently to the left of the family property in a near empty field. The octagonal wooden structure is affixed on a plot of fresh dug ground that Radon planted with yarrow. The Gate is split down the middle inviting viewers to look through it, to move through it and imagine what lies in the looming hillside behind. It is at once simple and highly articulated, sleek and intimidating, almost emblematic of the artist herself. An opening into the space, The Gate brackets the sun, a split octagon facing East to West. It prompts eights, and infinity, the unbounded potential of The Gate to both rise and set with the sun while also remaining firm and resolute on the land. Likewise, it encourages infinite iterations of itself and the discovery of new meaning. As the seasons shift and the wood begins to bow, and when it ultimately weathers and rots, Radon wishes to acknowledge the surreptitious bond she has created between viewer and sculpture.

The Gate will exist in stages, the very definition of opening up and opening into something more, and in these reincarnations, will hold both viewer and maker, alike, accountable. In conjunction, Radon is producing a Memorandum of Understanding between Radon and Layng on behalf of the Orchards as a print edition which includes instructions for The Gate’s reconstruction after its inevitable decay. This Memorandum will exist in the hopes that, upon following suit with the careful motions she has outlined, we might all gather again in the same place, in some time, to burn the decrepit remains and see the birth of another gate from the ashes.

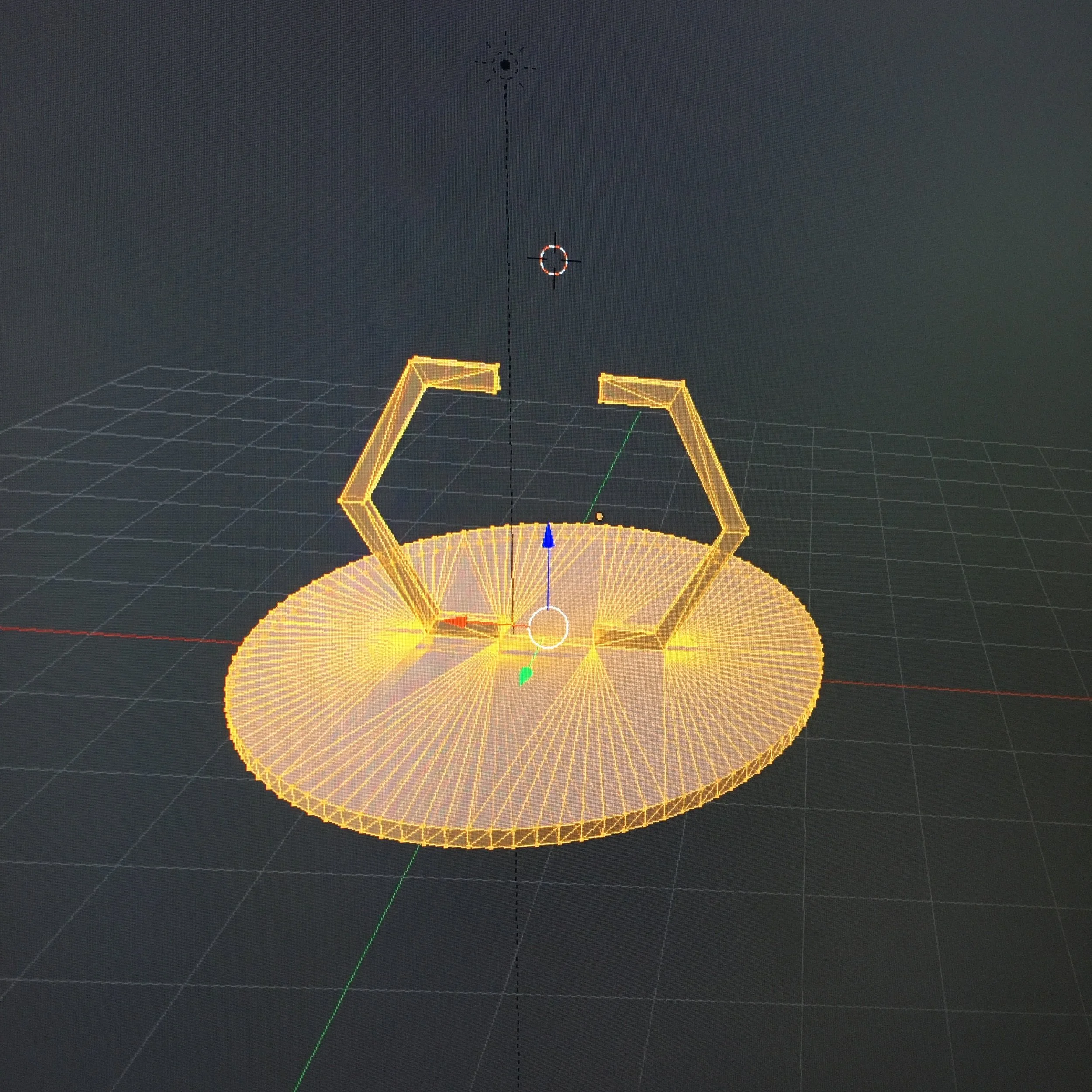

Lisa Radon. Digital rendering of the Immaterial Gate, 2018

This underlying contractual language of rebirth aligns with the linguistic approach Radon’s work often takes, as well as with The Orchards’ dedication to growth and forward momentum. The change that occurs will undoubtedly be unexpected; it could be drastic or it could be subtle, and it could occur first in the immediate environment of The Gate after which the structure would surely follow suit. The Memorandum details this commitment of labor and maintenance and releases it to the public, thus making everyone that comes into contact with the piece responsible to each other, to the work and to the earth. In holding us to different stages of continual interaction, it offers progress in the face of dissolution. It poses the question of what form the next iteration of The Gate will eventually take. It presents as an empty space, an invitation “to enter in to deeper in” teeming with a non-tangible materiality. Walking the line between the mystical and the earthly, The Gate and its affiliate tools provide to viewers and to Radon herself the means to navigate this world and another more transcendent one.

In curating, Layng considers the drastic difference in choosing to install for permanency as opposed to the transiency of a more traditional gallery space. The former, which is at the crux of The Orchards, is much more intimate in terms of labor, establishing relationships with fabricators and and cultivating care for the environment in which the work will exist. In this sense, any and all of the pieces on display compel us to engage in careful husbandry with the earth. Morgan Ritter’s The Sculpted Hand Which Strangles Its Creator was the first installation to be housed on the grounds and the only other permanent work, along with The Gate, that remains. Cradled between the pear and the plum trees, the work is a large, ceramic hand that lies fingers pressed into the ground and detached from the arm it once might have belonged to. The touch of the hand is visible in the earth, as is the earth’s wear and tear on the ceramic piece. The grass underneath has grown yellow and the fingers have delved into the dirt as they have settled. The heat from this year’s particularly blazing summer has begun to crack the ceramic surface adding the effect of time-worn authenticity to the piece. This symbiotic relationship is precisely the simultaneous effect Layng is seeking with his curation: a relationship with the earth in which the work gives back as much as it takes.

Akin to themes of temporality and transition explored in Radon’s work, The Orchards are forming a footprint online and, as a result, existing as much in the physical form as they do in a virtual format. On The Orchards website, one can experience the presence of two installations that are no longer physically on view. Rachel Ferber’s enter The Entree and Madeleine Barbier’s No crab. No wandering horse. They built a house for only one both wove together elements of sculpture and poetry, making use of the surrounding natural elements as their mediums. Ferber’s comical video installation, as playful as it was topical, features the artist making use of the abundant boysenberries in the fields to create “BYOB”, a natural beauty product with the cheeky tagline of “We become the punchlines of our own bad jokes.” Subsequently, Barbier’s elegant domes, staged uniformly on the floor of the open-air solarium, explore the idea of nets that are not nets and present a spatial ambiguity that retains a grounding force in the earthly and the mythic.

Considering The Orchards sustain themselves as a removed satellite from the localized arts community in Portland, showings are currently by appointment only. Layng would like to one day realize the gardens as a space open to the public daily, where community can come gather and spend a day in purposeful seclusion in the presence of art. Curatorially, The Orchards are also working towards expanding into a residency program in the near future, and in the spirit of transplanting and adapting, hope to work with more national and international artists, particularly ones who typically may not be used to showing work that lives outside in the elements. I’m reminded of a quote by essayist David Barnhill, which reads, “Our relationship to the earth is radical: it lies at the root of our consciousness and our culture and any sense of a rich life and right livelihood.” With this in mind, The Orchards bring to our contemporary art practice a weighted reminder to consider and appreciate one’s roots. Because in the end, when the sun sets, when the chickens come home to roost, everything will return, like the seasons, like The Gate, in a new but familiar form.

Images courtesy of Lisa Radon